The Day I Stood Before a Relic of the Messenger Muhammad

Although we have not had the opportunity to meet our Prophet ﷺ face to face, there is consolation in the traces that have been left to us. In this, and in everything, we have been blessed beyond measure.

At the base of the Roman aqueduct in Fatih sits a small Ottoman structure, its gray stone walls tucked in quietly under the vast arches, not drawing much attention to itself amongst the countless ancient edifices of the Old City. On the outside, it is unobtrusive, not attacking the senses, but exuding a tranquil nobility. On my walks past the towering aqueduct I have noticed it and wondered what it might have been. It never occurred to me to wonder what it was now: whether it was currently in use, whether there were some stirrings of life within its walls. Even after four years in Istanbul, I am still getting used to the idea that the centuries-old buildings that are naturally folded into the city’s landscape could still be providing the same social and educational services that they were built to provide, especially given the stifling secularism of the last century, which saw all religious institutions shut down, their ancient grounds left to decay and crumble. I am incredulous each time I hear about the way in which these long-abandoned structures are now being reappropriated and put to good use by those that know their true value — this, despite the fact that I have been privileged to personally benefit from these beautiful spaces and the new institutions that reside in them on countless occasions. I have been studying for four years at EDEP, a part-time seminary for female university students founded by Dr. Recep Şentürk and housed in the Hırka-i Şerif mosque complex. In that time, I have been able to attend conferences and classes at EDEP’s various sister programs, as well as at other educational institutions, each located in historic buildings of great religious and spiritual significance. Most recently, I was blessed to be able to attend al-Madina Institute’s year-long Suhba Program, which is held in the Valide-i Atik madrasa — a courtyard space that is like a garden from the gardens of paradise. So I have become familiar with dome-topped stone walls and the beauty they encompass. This particular madrasa, however — the Gazanfer Ağa madrasa, the one sitting in the shade of the great Roman arches — I had never had the opportunity to enter. But, alḥamdulillah, the Suhba Program, in all its baraka, opened those doors for me as well.

The Gazanfer Ağa madrasa was commissioned by Gazanfer Ağa, a chief steward of the household of Sultan Mehmed III, and completed in the 1590s. Its architect was Davut Ağa, a student of mimar Sinan, who later held his teacher’s position of Chief Architect of the empire. It is a relatively small madrasa, having housed up to 30 students at any given time. It was restored multiple times over the centuries, several times due to fire damage. Gazanfer Ağa is buried there, along with several others (amongst them would be some of the scholars who taught in the madrasa). In the 20th century, the madrasa was closed and its buildings used as a municipal museum and, later, a caricature museum. After Ataturk boulevard was built and its many lanes opened directly beside it, this place of religious education-turned-comic-museum was exposed to more traffic than it had ever been before. Most recently, it has been reappropriated and restored to its original educational purpose, having been passed into the hands of the Aziz Mahmud Hudayi waqf to use. There, they host classes on Islamic studies and provide students with the resources and means to pursue religious knowledge, filling the classrooms surrounding the central courtyard with the same sounds of learning as could be heard there centuries ago.

Once you enter the courtyard of the madrasa, something miraculous occurs: somehow, the walls, no more than two stories high, block out all the sights of the big city. Only the graceful arches of the aqueduct itself rise into view — everything else disappears. Just as it is in the Valide-i Atik madrasa, and many other madrasa courtyards, the greenery of the trees is the only thing to interrupt the wide expanse of blue sky. No skyscraper towers over this place, no anachronistic steel cuts into the view. It is as if the bustling highway just outside does not exist. The birds fly in and out with impunity, as comfortable as if they were coming from forest homes; they fill the flowering vines, or bathe in the central fountain. Upon entering, one is overcome with the conviction that this space is a rare spiritual oasis in the desert of this world. One has left behind the aggressive, hostile bustle of the proverbial rat race. The air here is infused with a calm that soothes the mind like a sweet musk. The senses drink deeply, taking in the nourishment of beauty: beautiful sights, beautiful sounds, beautiful scents. Parallel to every sensory pleasure that can be found here is a spiritual reality of greater beauty. The fountain spills over with a pleasant bubbling; even more beautiful are the voices raised in praise of the Prophet ﷺ. Light filters through the leaves in glorious mosaics of gold and green, but the light on the faces of the believers gathered here is brighter. At the center of this place there is a spiritual fountain to match the physical one: a source of clear, flowing water that is both purifying and nourishing. This is the spring of true knowledge, whose sounds are the sounds of remembrance that fill the air

In much the same way, the Suhba Program has acted as a spiritual oasis in my life and I am sure the same is true for all those who have been blessed to attend it. It is as though we, a caravan from amongst the caravans of Muslims, have reached a place of great richness, shade, and beauty after perhaps years of travel through barren lands with only the bare minimum to sustain us. For one year, we have been given the opportunity to rest, to tend to our wounds, to regain our strength, and to gather provisions for the rest of our journey. Going forward, God willing, we will take with us both the content of what we have learned from our studies as well as the habits of practice we have accrued by applying that knowledge. If we are wise in their use, these will sustain us until Allah ﷻ brings us to another oasis, or we pass out of this world. I promise you, reader: these spaces, these learning opportunities still exist, though they are rare. We must seek them out so we can heal, so we can feed our starving souls, so we can carry provisions to those who might not be able to reach such spaces. I believe the Suhba Program was designed with this purpose in mind. Throughout the year, our teacher, Shaykh Mokhtar Maghraoui, has been subtly but very consciously imbuing us with a strategy for survival, training us so that we build up a resistance to the many forces that besiege our souls. There is much about existence in this life that is corrosive to the soul, but if we are careful to preserve and apply the knowledge and practice we have gained, we will have a means to thrive even in the face of great difficulty.

I do not think it is an exaggeration to compare the world we inhabit today to a spiritual desert. There are those that might disagree with me, but I find much to reinforce the analogy. Like a desert, where there were once rivers, forests, pastures, and great civilizations, there remain only traces and ruins. Spiritually speaking, we are not now what we once were, nor is the world what it once was. I believe that the spiritual life of this world — the dunyā — was at its height, was at its most vibrant when our Prophet ﷺ inhabited it. Since he has passed out of it, I have no doubt that it has faded, though it lives on. How hard it is to imagine him now — in the world of cars, the Internet, nuclear weapons. Can we, with our scarred minds, imagine what it was like to take in the light of his countenance as he rode across the desert sands, and his companions marveled at how his beauty exceeded that of the full moon? Perhaps we cannot fill the image, but it gives me some comfort to believe that the grains of sand he tread might still exist, that the same moon still hangs in the sky. He was here, he lived on this earth, and he, like any person, left behind traces: āthār. The traces left behind a person are, of course, not the person itself: the value of mere physical objects is not comparable to the value of the living human soul that leaves its mark on them. Still, those that know what it means to love across time and space know how precious even the slightest traces of the beloved are once the beloved has moved on.

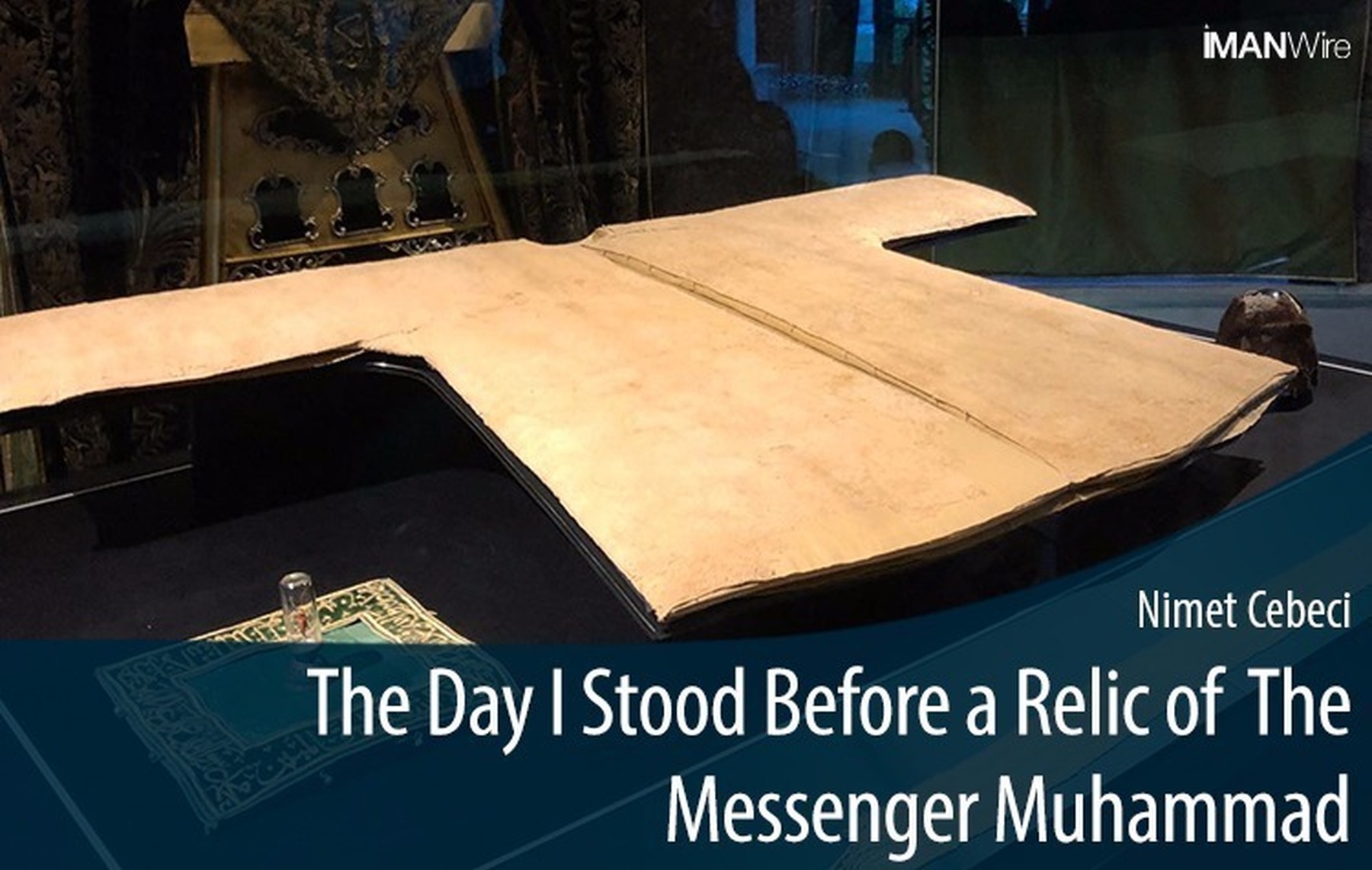

We have been separated from the physical presence of our Prophet ﷺ by centuries; we trek through this life looking forward to meeting him at the end of our journey, and breaking our thirst at his fountain. Most of us have never heard his voice, never looked into his eyes, never breathed in the musk of his presence. Yet, as we travel, we are sometimes afforded a glimpse of a place he may have passed, a physical sign that he had been there. Like oases, these traces are spiritual wellsprings: when we encounter them, we delight in their beauty and are refreshed. One example of these traces of his physical presence are his blessed strands of hair, which his companions collected and passed on through the generations. Another kind of trace are the articles of clothing he was said to have worn, similarly preserved and passed on by Muslims for centuries. Of these articles, two of the most striking examples — two cloaks that belonged to the Prophet ﷺ — can be found in Istanbul. When any relic fell into the hands of the Ottoman sultans, they preserved them with the most solemn respect, adorning their containers with gold and jewels, building mosques around them. The sultans made it a practice to visit these relics yearly in massive, celebratory processions. To this day, these relics are referred to as the mukaddes emanetler: sacred trusts. The cloaks are the most prominent of the relics found in Istanbul. One is kept in the Topkapı palace, in a large chest of engraved gold, in a beautifully adorned room into which visitors can peer from a distance. It has been a practice of the Turks to maintain a live recitation of the Qur’an in this space; a qārī (a reciter of the Qur’an) of the highest caliber sits in an adjacent chamber and recites continuously, switching in shifts so that the sound of recitation is never broken. The container of the cloak is still ceremonially opened once a year by the leader of the country on the 27th night of Ramadan, only to be gazed at for a few moments, then covered carefully in multiple layers of cloth and sealed again. On this occasion, the scent of musk is said to fill the room.

The second cloak is housed in the Hırka-i Şerif mosque, which was commissioned in 1847 by Sultan Abdülmecid for that specific purpose. It belongs to the descendants of the brother of Uways al-Qarani, to whom the Prophet ﷺ himself bequeathed the cloak. Uways was from the tribe of Mudar and lived in Qaran, in Yemen. His father passed away when he was a child and he was raised by his mother, whom he later cared for in her old age. His devotion to her care prevented him from leaving Yemen; thus, although he lived in the time of the Prophet ﷺ, accepted his message, and lived as a Muslim, he never had the opportunity to lay eyes on the Prophet ﷺ. This makes him a rare example of a contemporary of the Prophet ﷺ that is considered a tābiʿī, not a saḥābī. The Prophet ﷺ was informed of his filial piety, which prevented him from coming to be with the worshippers in Medina. Near the time of his ﷺ passing, the Prophet ﷺ charged ʿUmar (may Allah be pleased with him) with finding Uways and presenting him with his cloak. This was done, and throughout all the centuries thereafter the family of Uways al-Qarani have been the caretakers of this precious relic. They were invited to Istanbul in 1611 by Sultan Ahmet I, where they continued their tradition of sharing the cloak with the Muslims of their city, opening it to be viewed in a building they acquired for the purpose in the Fatih district. Later sultans built several structures specifically to house the cloak, but when these were found to be too small to accommodate its visitors, the Hırka-i Şerif mosque was built on the same piece of land. The cloak is still there today, and remains the responsibility of the al-Qarani family descendants; they are considered the rightful caretakers of this relic, with the Turkish government continuing the practice of the Ottoman Empire by providing the infrastructure to support them.

On the same day that we were blessed to feast and praise the Prophet ﷺ in the Gazanfer Ağa madrasa, we were all the more blessed to be able to make a private visit to the cloak or hırka of the Prophet ﷺ. We gathered outside of the Hırka-i Şerif mosque as the other believers were filtering out of it, and were led in by our generous hosts, up the spiral staircase and around the hallway to the high-ceilinged chamber where the cloak is kept. This viewing room is beautifully decorated with ornate tapestries and lamps, but somehow everything in the room appears dark except the cloak itself, which seems to glow with a bright, golden light, filling the room and the eyes of its beholder. The entire garment is a soft cream color, but upon close examination, one can make out the fine embroidery whose geometric pattern varies subtly in different places. A single layer of glass separates the viewer from the cloak, but one of the caretakers of the cloak is always standing by, observing the visitors and, after a time, softly ushering on those who are too overcome to move. On the day of our visit, the Suhba group filed in quietly, standing before the cloak in a semi-circle. Shaykh Mokhtar, in the middle of this semi-circle, fell to his knees. Of his beautiful, tearful prayer, what stayed with me was his reminder, in the form of the Qur’anic verse from Surat al-Hajj (22:32):

وَمَن يُعَظِّمْ شَعَائِرَ اللَّهِ فَإِنَّهَا مِن تَقْوَى الْقُلُوب

Whomsoever reveres the signs of Allah, verily, this is from the God-consciousness of the hearts.

In relation to this, I would like to point out, as Shaykh Mokhtar did before our visit, that the love and reverence we feel around āthār due to the love we feel for our Prophet ﷺ do not amount to worship of those āthār or of our Prophet ﷺ. To love is not to worship, to cry is not to worship, to long is not to worship. When these feelings become associated with a physical object as a symbol of the beloved, that is not an act of worship, neither is the original love of the beloved worship. To show reverence for what Allah ﷻ has created as a sign for us to know Him, and to love what He loves is an act of worshipping Allah ﷻ, not worshipping His creation. This is not a description of shirk, but of love of Allah, displayed through our behavior towards His creation, in a way that will please Him if we are sincere and He ﷻ accepts it from us.

I have had the opportunity, alḥamdulillah, to live across from the Hırka-i Şerif mosque and to visit the cloak of the Prophet ﷺ several times over my years in Turkey. This time was different, however. This time, I got to witness something unique: an athar kneeling before an athar. It is an established in our tradition that the righteous scholars are the inheritors of the Prophet ﷺ — he has no inheritors other than them. As a scholar, Shaykh Mokhtar is an athar of the Prophet ﷺ in the sense that he is an inheritor of the Prophet ﷺ and a preserver of his tradition, but, perhaps more strikingly, he is also an athar in the sense that he is a descendant of the Prophet ﷺ. To witness his state before the cloak of his Prophet and grandfather was a lesson for us all in love. Although we, like Uways (may Allah be pleased with him) have not had the opportunity to meet our Prophet ﷺ face to face, there is consolation in the traces that have been left to us. In this, and in everything, we have been blessed beyond measure. Our days here have truly been filled with beauty. As the Turks say, no matter how much shukr we make, how thankful we are, it would fall short. Where millions of words of gratefulness will not suffice, not much can be said beyond a simple: “alḥamdulillah.”

Faith & Spirituality Related Articles

5 Practical Steps To Get You Ready for Ramadan

As Ramadan is less than a month away, we might feel we often haven't done enough to prepare for it. Here are 5 things we can do right now during Shaban to make sure that we get the most out of Ramadan. The Prophet (Peace & Blessings upon Him & His Family) supplicated,” O Allah give us the blessings of Shaban and give us the treasure of Ramadan.”

Hajj at Home: Kindling the Spirit of Arafah

Even if we are not on Hajj this year, our situation is no different. We navigate through the complexities of our daily life, immersed in the never-ending responsibilities of work and family, inundated with the intrusions of technology and social media into every minute of our lives, moving from place to place and idea to idea.