Taking the Prophet as Your Spiritual Guide: Celebrating and Passing into the Prophetic Reality

Indifference to the celebration of the Prophet ﷺ denies the community the opportunity to unite upon his character and spirituality, in the face of so much pressure to move away from him. What are the tried and true methods to bring the Prophet ﷺ into our daily lives?

All things in creation suffer annihilation (faa’n) and there remains the face of the Lord in its majesty and bounty." (Holy Quran, Chapter of the All-Merciful: 26-27)

Today Muslims often conceive of a spirituality that is devoid of a temporal goal to be experienced in this life. This understanding is at odds with the earliest practitioners and sages of our tradition. Fanāʾ (annihilation of the soul) and baqāʾ (subsistence of the soul) were often depicted as mental and spiritual “states” (aḥwāl),“stations” (maqāmāt), “steps” (manāzil), or “fields” (maydān) towards the end of one’s spiritual journey (Sulook).1 This hierarchical ordering served as the roadmap for the progressive experiential stages of the spiritual journey. In most schemas, fanāʾ is followed by baqāʾ, with the latter being seen as a sobering, but more advanced, stage.2 The spiritual wayfarer (salik) succeeds in annihilating his base egotistical (nafsi) attributes and loses all awareness of earthly existence; he then, through the grace of God, is revived, and the secrets (asrar) of the divine attributes are revealed to him. Only after regaining full consciousness does he attain the more sublime state of baqāʾ (subsistence), and finally becomes ready for the direct vision of God. Today we rarely hear of fanā openly, and even in Sufi orders (turuq) it is only discussed it is only discussed in vague terms. Much more emphasized are the concepts surrounding fanāʾ fil Rasul, by which a deep love for the Messenger of God ﷺ embraces a spirituality beyond any persons or living guides. Is this a concept that is textually rooted in the Islamic Spiritual Tradition or a dynamic shift in focus at a historical point in time? Moreover, how would we benefit by setting a spiritual goal with a focus of bringing the Prophetic presence into our lives?

A TIMELINE OF THOUGHT & SPIRIT

Abu Yazid Bistami (d. 261AH) and Al-Kharraz (d. 279 AH) were arguably the first Sufi formulators of the theory of annihilation and subsistence of the soul, but it was Al-Junayd's speculative usage that formed a more coherent thought structure.3 The twin concepts of fanā' and baqā' were amongst the earliest formulations of the concept of tawḥīd (Divine Unity). Often these intellectual concepts were based upon practical experiences of fanā' from personal accounts. The doctrinal and socio-political ramifications of the two schismatic interpretations of the nature and role of fanā' and baqā' as expressed by the 'Sober' School of Baghdād and the 'Intoxicated' School of Khurāsān have had ramifications up until our own time. The theories of the two Sūfī masters generally accepted as the principle advocates of these opposing doctrines were Abū'l-Qāsim al-Junayd (d. 298), the definitive exponent of the doctrine of Sobriety; followed by the counter-claims of the martyr Husayn ibn Mansūr al-Hallāj (d. 309), often described as the ecstatic intoxicant par excellence. The interplay of politics factored into the opposing interpretations of the religious life of Muslims, as the political machine endorsed certain views and suppressed others.4 An elder in the Baghdad school, and a one-time spiritual mentor to al-Hallaj, Sahl al-Tustari (d. 283 AH) stood in some respect in the middle and posited a notion that would eventually change the course of Islamic spirituality.5 Al-Tustari, as well as al-Hallaj, were respected scholars in the Traditionalist (Ahl-i-Hadith) and Hanbali circles of their time. While we have documented evidence elsewhere, al-Tustari introduced the doctrine of the Muhammadan light (Nur al-Muhammadiyya)6, while al-Hallaj was an early depositor to the notion of the Perfect Man (Insan Al-Kamil)7. It was these early concepts that continued to promote a profound following of the exemplary life (Sunna) of the last Prophet ﷺ, and to which we now turn.

We have discussed the definition of fanā found in classical writings, but in contemporary practice one rarely hears of fanā in God; instead, one speaks of fanā in one's shaykh and fanā in the Prophet.8 In the later generations, this idea persisted and found its full flowering in the doctrines of “The Greatest Shaykh” (Shaykh Al-Akbar) Ibn Arabi (d. 638 AH). As an avid student of Ahadith (Prophetic Narrations), Ibn Arabi’s doctrine was incorporated into narrations of his notion of the Prophetic Reality stating, "Muhammad's wisdom is uniqueness (fardiya) because he is the most perfect existent creature of this human species. For this reason, the command began with him and was sealed with him. He was a Prophet while Adam was between water and clay9, and his elemental structure is the Seal of the Prophets"10. The Akbarian School further developed the ideas of the Perfect Man (Insan Al-Kamil) and the Muhammadan Reality (Haqiqat Muhammadiyya)11 that continue to figure largely in the everyday spirituality of Muslims around the globe. Some have posited that the concept of annihilation in the Messenger, and spiritual concentration upon the Prophetic essence as regular discipline for spiritual seekers, emerged in what is known as the revivalist "Muhammadan Path" (al-tariqa 'l-muhammadiyya). While this trend was widespread, it was the teachings of 17th century Ahmad al-Tijani in the Maghrib (which were also influential in Senegal and as far reaching as the Malay Archipelago), and of the one time resident of Fez turned spiritual nomad, Ahmad ibn Idris, that served as springboards for a number of different spiritual orders. In the words of one academic, "The two Ahmads both stressed that the purpose of dhikr was union with the spirit of the Prophet ﷺ, rather than union with God—a change which affected the basis of the mystical life".12 Through their famous prayers, litanies, and writings, they no doubt played a huge part as many scholars did in reviving this practice13, but it would be folly to not see their focus as a practice rooted in that of the Prophet’s own companions, some of whom dedicated all of their spiritual practice to sending prayers upon the Prophet.14 Moreover, we see this depicted in the dreams and wakeful visions of the righteous that behold the image of the Prophet ﷺ. It is narrated that when the polymath and arguably a reviver in the faith, Imam Jalaluddin Suyuti (d. 911AH), heard a narration, he would know whether it was authentic or not. Someone asked (how does he do so), so he replied, "After listening to the tradition, I look towards the Prophet’s ﷺ face. If he is joyous, I understand it to be a Hadith and if his face is gloomy then I know it’s not a Hadith”.15 Examples of such experiences frequently occur in works on Sacred Tradition, which only adds to the point that any historical trend was shaped by early canonical writings.16

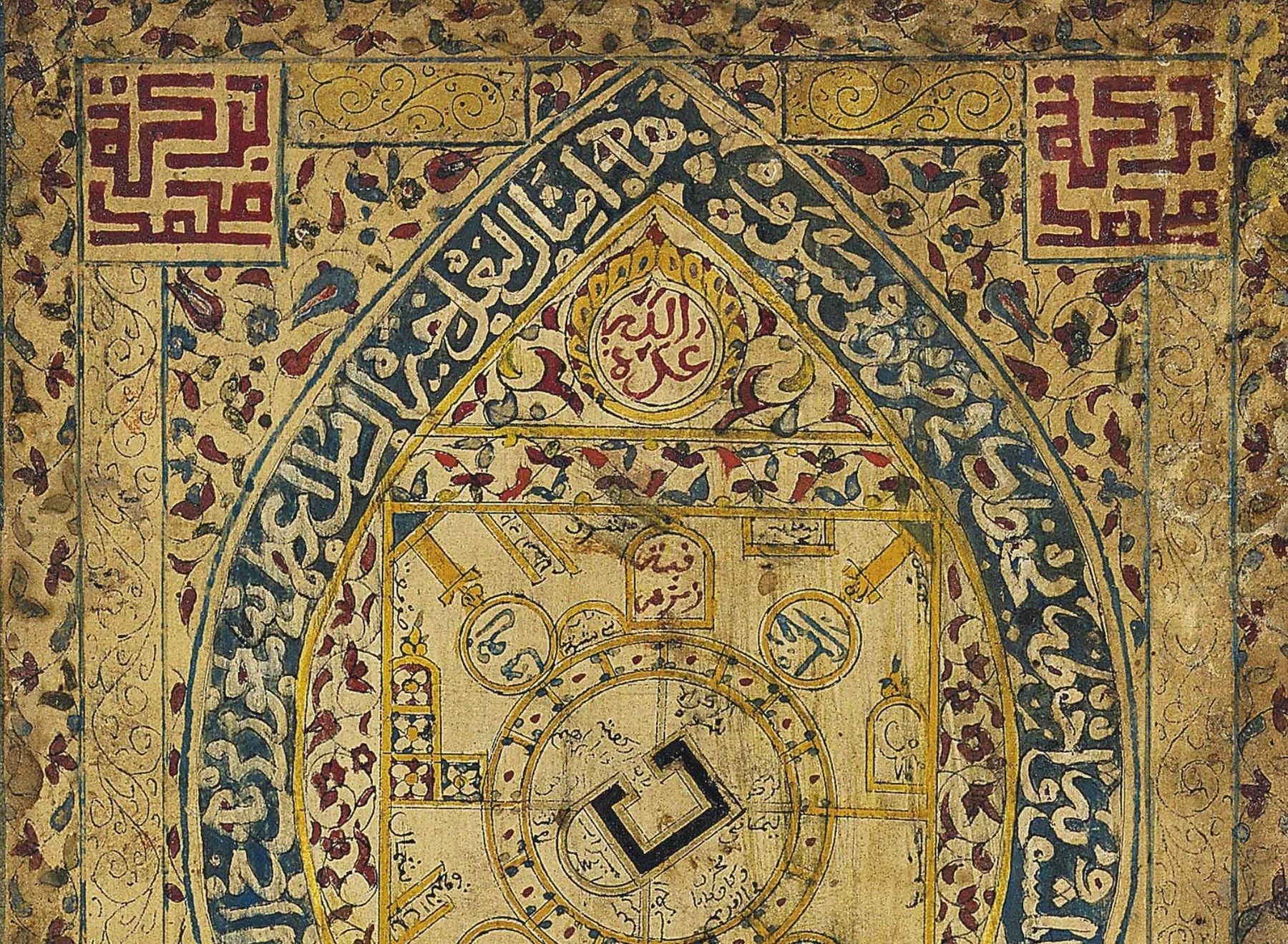

What is often overlooked is that during this period the introduction of the printing press made substantial inroads prior its official commencement in the 19th century in the promotion of spreading the practice of veneration of the Prophet ﷺ as a spiritual practice.17 Some of the most popular books of the period found from Morocco to India were titles that focused the reader upon the Prophet ﷺ. The Al-Shamā'il Muhammadiyyah (The Appearance of Muhammad ﷺ) by Al-Bukhari’s (d. 256 AH) student Al-Tirmidhi (d. 279 AH), and the Spanish Scholar Qadi 'Iyad's (d. 544 AH) Kitab al-shifa bi-tarif huquq al-Mustafa (Book of Healing by Acquainting [the Reader with] the Rights of the Chosen One) exerted a great deal of influence on the popular veneration of the Prophet ﷺ throughout the Muslim world. Outside of the known works of traditions by Bukhari and Muslim (d. 261 AH), they are likely the works that have garnered the greatest amount of scholarly commentaries spanning vast geographic locations and time periods.18 The Moroccan Shadhuli Shaykh Muhammad ibn Sulayman al-Jazuli’s (d. 870 AH) popular devotional handbook, Dalaail u'l Khayraat Wa Shawaariq u'l Anwaar Fee Zikri's Salaat Alan Nabiyyi'l Mukhtaar (The Waymarks of Benefits and the Brilliant Burst of Lights in the Remembrance of Blessings on the Chosen Prophet), became a guide to the invocation of blessings on the Prophet ﷺ. Al-Jazuli’s work was structured by days and affected later works on Prophetic invocations such as the famous Al-Hizb al-A’zam wa ’l-Wird al-Afkham (The Supreme Daily Remembrance and the Noble Litany) by Mulla Ali Al-Qari (d. 1014 AH). Today this genre of devotional works continues to be widely used throughout the Muslim world. To reach the masses such works and mystical ideas were fodder for thousands of poetic expressions. From the time when the Prophet ﷺ wrapped the companion Ka’ab ibn Zuhyar in his cloak (Burdah), poetic praise of the greatest of creation has been a consistent art form throughout every age of Islamic civilization.19 Al-Busiri’s al-Kawākib ad-dhurriyya fī Madḥ Khayr al-Bariyya (The Celestial Lights in Praise of the Best of Creation) gained such popularity that its verses once graced the walls of the Prophet’s ﷺ Mosque in Medina (today two lines remain).20 Understanding that there was a currency of ideas, a similar book by the same title was said to have been written in Iran at about the same time.21 The Mawlid became a literary genre in its own right. Narrative accounts and panegyric poems, composed by scholars such as Ibn Kathir (d. 744 AH) and Al-Barzinji (d. 1177 AH), commemorated the nativity of the Prophet ﷺ. One finds within such devotional works and manuals the influence of Akbarian thought and the concept of the Perfect Man as it relates to fanāʾ fil Rasul. For example, Al-Jili is quoted in some of these works stating, that by loving Muhammad ﷺ one enters the secrets of existence and enters annihilation (fanā), "The Messenger is in you as a substitute for you, so you may take on the disposition of his noble reality”. Textual evidence like this highlights how prayers upon and meditation of the Prophet ﷺ as a mystical experience predates the 17th century trend known as the Muhammadan path, and its chief proponents by several centuries.22

CONNECTING TO THE SPIRIT OF THE PROPHET IN YOUR DAILY LIFE

From the above historical outline, we can gain an understanding of tried and true methods to bring the Prophet ﷺ into our daily lives:

- Seeking Illumination through Revelation: Simply reading the Quran anew from the standpoint of understanding that every utterance first occurred via the blessed tongue of the Prophet ﷺ can be transformative. The Quran itself states that revelation descended upon the heart of the Prophet ﷺ.

- Speaking Affirmations: An affirmation is a self-fulfilling prophecy. Gradually, you begin to think and act in ways that support the affirmation and accelerate its manifestation. Maintaining an ongoing dialogue through the devotional practice of invocation of blessings on the Prophet ﷺ is the surest method, as outlined in Quranic and Prophetic practice, of altering your state. Just as a parent treasures every expression of affection from a beloved child, so too is the Prophet ﷺ touched by your every expression of loving devotion on a weekly basis as indicated in authentic statements.23 Popular manuals such as the Dalaail u'l Khayraat are a great start.

- Looking At the Prophetic Mirror Within You: Reading and studying works mentioned such as the Shamail and the Shifa provide a tool to transform your life, using it as a mirror on your own life, personality traits and relationships. Like using a mirror, by learning about and acting upon Prophetic qualities, we can beautify ourselves.

- Be In His Presence: Practicing the presence means keeping your love for the Prophet ﷺ in your thoughts as often as possible. Annihilation in the Prophet ﷺ is the way to true mystical experience. Al-Jili instructs us to concentrate on the Prophet ﷺ, picturing him before our eyes, as the means to this end.

- Serving the Message, By Serving Others: Enriching your inner life is only half of the equation. Taking part in service (Khidma) is a huge part of spreading Prophetic love and elevating your states. If the peace and unconditional love you feel in meditation is not expressed through your every action, then you are not truly living a spiritual life. The goal after all is not to avoid the world, but to live in it more consciously and fully in ways that serve humanity.

TAKING THE MAWLID AS A SEASON OF RENEWING YOUR RELATIONSHIP

Mawlids (Commemorations of the Birth of the Prophet ﷺ) have their origin in Early Islam. The second Caliph, Umar, reportedly thought of taking the Prophetic birth ﷺ as a starting point for the Islamic calendar.24 Historic traces also exist during Abbassid rule, with the noted traveller Ibn Al-Jubayr (d. 614 AH) describing celebrations every Monday of the month of Rabi’ al-Awwal at the site of the Prophet’s ﷺ birth in Mecca in 579 AH.25 The Ismaili-Shi’i Fatimids celebrated the anniversaries of the Prophet ﷺ and members of his Prophetic House (Ahl Al- Bayt) in Egypt and surrounding domains. Although some believe they initiated this observance, the Fatimid mawlids took place only at the royal court in broad daylight and bore little resemblance to the contemporary practices.26 In addition, the only mawlid that continues without reference to a particular space is that of the Prophet ﷺ. Celebrated all over the world (with the exception of only two Muslim countries), the celebrations are not fixed on the 12th of Rab’i Awwal, and occur on different dates throughout the year. Sunni historians and theologians trace the origin of the mawlid as we know it to a celebration in Arbela, southeast of Mosul, in 622 AH, arranged by Emir Muzaffar al-Din Kokbori/Kokburii (d. 631 AH), the brother-in-law of Salahuddin Al-‘Ayubi (d. 589) and a famous general who fought both Crusader and Mongol forces in his lifetime.27 Around the same time, the scholar Abu Al-Abbas al-Azafi (d. 651 AH) introduced the celebration in the Maghreb.28 This celebration bore many of the features of the modern-day mawlid. Under the rule of the Ayyubids, the mawlid took root there and spread from there throughout the Muslim world.29 This appears to indicate that Fatimid influence on the popular religion of the masses was limited.

The glorification of the Prophet ﷺ, and the doctrines of the eternal Muhammadan reality, have a very long history, culminating in the teachings of Ibn Arabi and Abd al-Karim al-Jili. The glorification of the Prophet ﷺ has since taken root in many popular forms of devotion. The influence of fanāʾ fil Rasul on popular Islam across the Muslim world is still quite palpable, but for many western Muslims who follow a “sanitized” version of the faith, they are left without a clear path in their respective spiritual journeys. Whether rooted in earlier hero veneration, or a post-occupation celebration meant to unite religious identity amidst ruins, the mawlid can be a powerful symbol of re-connecting the community to the mystical version of the Prophetic Practice or imitatio Muhammadi.30 There are parallels today to the Muslim world that first saw the rise of the Mawlid. Some scholars have suggested that the strong mawlid leanings in the Sunni world can be partially attributed to growth in urban communities that re-emerged after the trauma of war and occupation. Today, millennial Muslims are choosing to move to urban centers, where they are often at odds with older, established communities. The popularity of trade guilds of the futuwwa orders, for whom the Prophet ﷺ and Ali were the exemplary personas, highlights that there were spaces of community that formed outside of the mosque.31 Today in America, every major city has efforts to establish Muslim communities that are not beholden to a particular space. The merits of taking the Mawlid season as a time to educate ourselves, our children, and our communities about the contributions of the Prophet ﷺ cannot be overemphasized. We exist in a narcissistic age where most five year olds get any toy they want while celebrating their own birth (ironically, some scholars who still oppose the Mawlid now allow for the celebration of one’s own birth). We still live in a community that is mistakenly indifferent to the celebration of the birth of our Prophet ﷺ. This indifference denies the community the opportunity to unite upon the character and spirituality of the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, in the face of so much pressure to move away from him due to constant critiques of his life and practices.32 Despite the debate about the merits of celebrating the birth of our Prophet ﷺ, each of us should dwell upon the place of the Prophetic Presence in our lives; see the merit in moving spiritually, stage by stage, in perfecting ourselves in the mirror of Prophecy; and looking to set goals in our spirituality by passing away into the Muhammadan Reality.

1. Anjum, Ovamir. “Sufism without Mysticism: Ibn al-Qayyim's Objectives in Madarij al-Salikin.” The Madarij being a commentary on Khwaja Abdullah Ansari of Herat Manāzel al-Sā'erīn. For further reading see “Stations of the Sufi Path, The One Hundred Fields (Sad Maydan) of Abdullah Ansari of Herat”, translated by Nahid Angha.

2. Mojaddedi, Jawid. “Annihilation and Abiding in God.” In Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE. Edited by Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, and Everett Rowson. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2011.

3. Martin, David Ludwig. “Al-Fanā ' and Al-Baqa' in the Work of Abu Al-Qasim Al-Junayd Al-Baghdadi” Dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles (1984)

4. Wilcox, Andrew. “The Dual Mystical Concepts of Fanā' and Baqā' in Early Sūfism.” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, vol. 38, no. 1, 2011, pp. 95–118.

5. Mason, Herbert W. (1995). Al-Hallaj. RoutledgeCurzon. p. 83.

6. See Qur’an commentary by Muqatil (d. 767), a Zaydi Shiite: Paul Nwyia, Exegese cora nique et langage mystique, Recherches de l'Institut de Lettres Orientales, vol. 49 (Beirut: Dar el-Machreq, 1970), 95. Among the Sunnis, the doctrine of the Muhammadan light was first expounded by the Sufi Sahl al-Tustari (d. 896): Gerhard Bowering, The Mystical Vision of Existence in Classical Islam: The Qur'anic Hermeneutics of the Sufi Sahl at-Tustari (d. 283/896) (New York: de Gruyter, 19).

7. Al-Hallaj, Translated by Aisha Bewley. “The Tawasin”, Diwan Press, pp. 1–3

8. Hoffman, V. (1999). Annihilation in the Messenger of God: The Development of a Sufi Practice. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 31(3), pp. 351-369.

9. Sahih hadith states: “Truly I was [already], in the sight of Allah, the Seal of Prophets, when Adam was still kneaded in his clay. I shall inform you of the meaning (ta’wil) of this. It is the supplication of my father Ibrahim (Q 2:129) and the glad tidings of my brother `Isa to his people (Q 61:6); and the vision my mother saw the night I was delivered: she saw a light that lit the palaces of Syro-Palestine so that she could see them.”Narrated by Ahmad, Musnad al-Shamiyyin, from al-`Irbad b. Sariya (al-Zayn ed. 13:282 §17086, 13:285 §17098; al-Arna’ut ed. 28:382 §17151, 28:395 §17163), among others.

10. Ibn ‘Arabi,Translated by Aisha Bewley. “The Seal of the Unique Wisdom in the Word of Muhammad” (https://bewley.virtualave.net/fusus27.html)

11. Ibn 'Arabi. Al-Futihat al-makkiyya (Beirut: Dar Sadir, 1966), pp. 1:134-35.

12. Trimingham, J. Spencer. “The Sufi Orders in Islam”. (Oxford, 1971), pp. 106.

13. See “On The Path Of The Prophet: Shaykh Ahmad Tijani and the Tariqa Muhammadiyya Paperback – April 26, 2015 by Zachary V Wright; “The Enigmatic Saint: Ahmad Ibn Idris and the Idrisi Tradition” by R.S. O’Fahey.

14. See Traditions such as this that indicate this practice and it’s many rewards, “Ubay bin Ka’ab (may Allah be pleased with him), who said; ‘I said, ‘O Messenger of Allah, I supplicate often, so how much of my supplication should I devote to you?’ He replied, ‘as you desire’. I said, ‘a quarter of it?’ He said ‘as you desire, but if you were to increase upon this, it would be better for you.’ I said, ‘half of it?’ He said, ‘as you desire, but if you were to increase upon this, it would be better for you.’ I said, ‘two-thirds of it?’ He said again, ‘as you desire, but if you were to increase upon this, it would be better for you.’ Finally I said, ‘and if I dedicate my supplication in its entirety to you?’ He said, ‘then your needs will be satisfied, and your sins forgiven.’ (Source Musnad Ahmed, validated as authentic (Sahih))

15. Thanwi, Ashraf Ali. “Malfoozat Hakim al-Ummat (Urdu)”. Vol.7, pp.109-110, Saying no. 171.

16. See, “It was narrated that Abu Hurayrah said: I heard the Prophet (peace and blessings of Allaah be upon him) say: “Whoever sees me in a dream will see me when he is awake; the Shaytaan cannot take my shape” (Narrated by al-Bukhaari, 6592; Muslim, 2266). According to a report narrated by Ahmad (3400): The Shaytaan cannot resemble me.” Al-Haafiz Ibn Hajar said: We have narrated it with a complete isnaad from Ismaa’eel ibn Ishaaq al-Qaadi from Sulaymaan ibn Harb – who was one of the shaykhs of al-Bukhaari – from Hammaad ibn Zayd from Ayyoob who said: If a man told Muhammad (meaning Ibn Sireen) that he had seen the Prophet (peace and blessings of Allaah be upon him) [in a dream], he would say, “Describe to me the one whom you saw.” If he gave a description that he did not recognize, he would say, “You did not see him.” Its isnaad is saheeh, and I have found another report which corroborates it. Al-Haakim narrated via ‘Aasim ibn Kulayb (who said), my father told me: I said to Ibn ‘Abbaas, “I saw the Prophet (peace and blessings of Allaah be upon him) in a dream.” He said, “Describe him to me.” He said, “I mentioned al-Hasan ibn ‘Ali and said that he looked like him.” He said, “You did indeed see him.” Its isnaad is jayyid. Fath al-Baari, 12/383, 384.

17. Aqeel, Moinuddin. “Commencement of Printing in the Muslim World: A View of Impact on Ulama at Early Phase of Islamic Moderate Trend”. Kyoto Bulletin of Islamic Area Studies, 2-2 (March 2009), pp. 10–21.

18. See Bewley, A'isha Bint ʿAbdurrahman. “Muhammad Messenger of Allah: ash-Shifa' of Qadi ʿIyad” (Granada: Madinah Press, 1992).

19. Sells, Michael and Sells, M.J. “ Bānat Suʿād: translation and introduction”, Journal of Arabic Literature Vol. 21, No. 2 (Sep., 1990), pp. 140-154.

20. "BBC – Religions – Islam: al-Burda". Retrieved 2016-12-17.

21. Cornell, Vincent. “The Logic of Analogy and the Role of the Sufi Shaykh in Post-Marinid Morocco,” International Journel of Middle East Studies (1983) pp. 90. Also, see Uthman, Muhammad. “Mirrors of Prophethood," 477-479, 507. In Tabrfat al-dhimma fi nush al-umma, pp. 36-57.

22. Cornell, Vincent. "Mirrors of Prophethood: The Evolving Image of the Spiritual Master in the Western Maghrib from the Origins of Sufism to the End of the Sixteenth Century" (Ph.D. diss., University of California at Los Angeles, 1989), pp. 573.

23. Jila-ul Ifhaam, by Ibn Qayyim and stated as being recorded from Imam Tabarani’s collection.

24. Fitzpatrick, Coeli & Walker, Adam Hani. “Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God”, p. 365.

25. Ibid

26. Fuchs, H. "Mawlid," El 1, 3:420.

27. Nicolle, D. “The Crusades”, Osprey Publishing, Oxford.

28. Katz, Marion Holmes. “The birth of the prophet Muḥammad: devotional piety in Sunni Islam”, Routledge, 2007, p. 10 and throughout.

29. Ibn Khallikan, cited in Fuchs, "Mawlid," pp. 420. Gustave E. von Grunebaum, in “Muhammadan Festivals” (New York, 1951), p. 73.

30. Cornell, Vincent. "Mirrors of Prophethood: The Evolving Image of the Spiritual Master in the Western Maghrib from the Origins of Sufism to the End of the Sixteenth Century" (Ph.D. diss., University of California at Los Angeles, 1989), pp. 573.

31. Hodgson, Marshall. “The Venture of Islam”. Vol. 2: pp 130.

32. See Sbaihat, Ahlam. "Stereotypes associated with real prototypes of the prophet of Islam's name till the 19th century". Jordan Journal of Modern Languages and Literature Vol. 7, No. 1, 2015, pp. 21–38

Academic Related Articles

Sayyidah Nafisah: The Saintly Lady of Egypt

Often underdiscussed among Muslim circles in the West are the righteous and scholarly women among the pious early Muslims. Out of the many other stellar women from early Islamic history worthy of mention, Sayyidah Nafisah (may Allah be pleased with her), already adored by millions of Egypt, was a shining star that should be known by all.